Horror week on Outwardfilmnetwork.com from Outward Film Network on Vimeo.

Category Archives: A Week of Horror

Hour of The Wolf: Ingmar Bergman’s claim to be one of the greatest horror filmmakers in cinema

If horror films, at their most basic level, engage our most primal fears about who we are and what could threaten us then the great Swedish auteur, Ingmar Bergman, might just have been overlooked as a master proponent of this cinematic exercise. While Bergman only made one official horror movie (1968’s Hour of the Wolf in titular reference here), much of his work is inflected with genre tropes and his searing use of abstract imagery may well have prefigured the artistic nightmares of David Lynch and David Cronenberg.

Bergman is thematically associated with art-house philosophising, spiritual emptiness and human drama but his films have often been at their most potent when exploring the darkness that we normally link to horror masters such as John Carpenter, whose sublime 1982 film The Thing shares much of Bergman’s concerns about group dynamics. While Hour of the Wolf is the most explicit in creating a classic horror scenario (an artist losing his grip on reality) you can find other distinct genre traditions in his more oblique narratives. Take 1980s From The Life of the Marionettes which, with its warning light reds and dangerous, menacing close-ups reminds us of the mesmeric nightmares of Lynchian cinema. Or Cries and Whispers (1972), ostensibly a family drama about the ravages of terminal illness, but structured like a haunted house movie with the protagonists all trapped within the confines of a location as an unseen foe rips them apart. Even his celebrated masterpiece, the existential road movie Wild Strawberries (1957), plays liberally with a Bunuellian sense of the macabre, particularly in the compelling dream sequence at the beginning (the turning over of the body sends chills down my spine every time).

Wild Strawberries

Bergman also evidenced interpretations of both the classic horror literature of Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker and thereby the golden era of Hammer House, by fashioning his own monster in Winter Light (1963). In small town priest Tomas Ericsson (a consummate performance of existential falling out from Gunnar Bjornstrand), Bergman made his own ‘Frankenstein’s monster’: a cold, spiritually empty individual who is seemingly only able to ape human behaviour from observation, not intrinsic empathy. Wanting to belong to the greater society, he is unable to truly relate and so ends up destroying everything around him.

Winter Light

But perhaps Bergman’s greatest employments of horror come in his three films The Virgin Spring (1960), Persona (1966) and The Seventh Seal (1957). Of this trio, The Virgin Spring is structurally most recognisable as a horror film (and was in fact the inspiration for Wes Craven’s Last House On The Left, 1972) as a patriarch wreaks vengeance on the miscreants who raped and killed his daughter. But Persona, about an actress and a nurse who start to share consciousness during a respite retreat, has something of the terrifying duality of Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers (1988) and the concept of split personalities is no stranger to horror cinema. And the bleak, plague-ridden vista of The Seventh Seal, brooding with a superstitious fear in a medieval world where science has not yet developed to offer the comfort of knowledge, has a terror that is so fundamental to our own sense of self, it has more effect than any splatter-house flick or ghost thriller that you might more readily associate with horror. The film is even recalled through Christopher Smith’s similarly themed Black Death (2010) and perhaps the sight of Death playing games with mortality is crucial to all truly efficacious spine-tinglers.

The Seventh Seal

Prison

In conclusion, I turn to Bergman’s little-discussed ‘film-within-a-film’ riff Prison (1949) that I think defines the great filmmaker’s role in shaping horror cinema indefinitely. On the surface, we can see many different genres and many different stories at work in Bergman’s cinema but, as one character remarks at the start of Prison to the notion that Earth is actually hell, “Satan doesn’t have a platform, that’s the secret of his success.” There is a devil in all great horror cinema, the devil of the dark heart of humanity, and it is this that simmers under the surface of Bergman’s tremendous body of work.

Interview #13: Wyrmwood

The filmmakers behind Australian zombie film Wyrmwood Road of the Dead describe it as: “A rip-roaring Ozzie classic with beer and people being very sweary.” If first impressions are as important as they say, then Tristan and Kiah Roache-Turner’s debut feature leaves an indelible scar on the consciousness of any genre fan, the bold vision of what genre cinema can be embraced with great affection by the filmmakers.

The filmmakers behind Australian zombie film Wyrmwood Road of the Dead describe it as: “A rip-roaring Ozzie classic with beer and people being very sweary.” If first impressions are as important as they say, then Tristan and Kiah Roache-Turner’s debut feature leaves an indelible scar on the consciousness of any genre fan, the bold vision of what genre cinema can be embraced with great affection by the filmmakers.

During the course of our conversation, the brothers looked back on the Wyrmwood experience while keeping their one eye on the future. As Kiah explained: “Usually it seems like filmmakers take about three films to find their tone. I do feel that Wyrmwood is kind of a pastiche of Romero, George Miller and all these people. It is certainly bursting with original energy, but I think Tristan and I have to make a couple of other films before we really find what our style is as directing brothers. But it will be fun finding that tone!”

Why a career in film? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

TRT: I’ll jump in there! I became obsessed with film when I was thirteen maybe fourteen; absolutely obsessed with Raiders of the Lost Ark and Star Wars. We had a family friend who had thousands of movies, and so I started devouring Apocalypse Now, Blade Runner and Taxi Driver at a very young age. I developed this weird OCD obsession with filmmaking and as soon as we got our first camera when we were fifteen or sixteen Tristan and I just started making films together.

The first film we made I chopped him up and put him in a bag. When our mom saw that film she started screaming and crying. It was then that we realised what a strong reaction we could get from an audience, whether it was our mother or somebody in Spain, which we would find out about twenty years later. So we just started making films: short films and music videos for ten, fifteen years and then inevitably we would wind up making a feature. We sat down and decided to make a zombie film which took us four years. We started in 2010 and here we are now talking about it.

Why do you think the Zombie monster and the apocalypse continue to endure within narrative fiction?

KRT: It is a difficult question to answer and we have thought about it a fair bit, because we are in that genre now. I think people have an obsession with the end of the world, and zombies represent the end of the world. The apocalypse is a fascinating thing especially with global warming and all that bollocks. But if you move all of that intellectualisation aside, one of the things that people love about zombie films is that you are in a world where you can blow your neighbours head off with impunity. There are are shuffling corpses wandering around and suddenly you are in a live action video game where you can pick up a shot gun, run out the front door and cause a bit of mayhem. It is like a game and you have to survive. One thing that people love is the video game concept, which is a challenge and it can also be adventurous. Years ago Tristan and I used to have a big obsession with shoot ‘em ups, and zombie films are basically living through a first person shoot ‘em up. Hey what do you reckon Tristan…did I answer that one well?

TRT: Hell yeah! Me personally I just love shotguns. I just love the idea of having something coming towards you that wants to kill you, and you have not only the right but the responsibility to blow the damn thing away! [Laughs]

Reflecting on your experience in the director’s chair for your feature debut, how did the expectations compare to the reality?

KRT: What do you reckon Tristan?

TRT: I reckon this movie turned out so much better than I expected it to. I always thought it was going to be awesome; a good romp and good fun. I thought it was going to be so patchy and rugged, but it actually doesn’t look like a movie that was filmed over four years, and it doesn’t seem like the script was created in this haphazard, completely transformational way that changed dramatically over the time that we shot. It seems to be a pretty cool complete little piece, and for me it was great. The amount of articles and reviews that have been written about it, I wasn’t expecting at all, and so it exceeded all expectations. It has been a great ride, and it has been humbling. It makes me think the world is a really beautiful place… It has been great!

The British setting of Under the Skin and Nina Forever afforded these films a certain feel. What does the Australian setting bring to the Wyrmwood and is the identity of the film intrinsically linked to its spatial settings?

KRT: Definitely, and just to say that I loved UNDER THE SKIN. I fucking adored it. It is one of my favourite films and I could never make a film like that. It is brilliant! But, yeah the landscape and the country should be intrinsic to the art of the film.

TRT: With Wyrmwood what we really wanted to do was to make a film that celebrated Australianess, like they did back in the seventies with Mad Max and all those Ozploitation films. There has been a tendency in the last couple of decades for Australian filmmakers to kind of make these films with American accents, and I think that is where it started to pander to an American audience. But we didn’t want to do that. We wanted to make a rip-roaring Ozzie classic with beer and people bring very sweary. We wanted to make a zombie film where the lead guy is a mechanic from Bankstown, which is a suburb in Sydney where tough blokes come from; where the real Australians come from. It was important for us to shoot in the bush because most of the zombie films that you see, whether it is World War Z or 28 Days Later which is London, they are always shot in those settings. It was very important for us to go out into the bush and the Blue Mountains and film a landscape that is deeply Australian. We were also very lucky that we were able to find someone like Leon Butchill so that could we could also bring the indigenous side of things to the film, and make it a fully rounded Australian experience. So that was very important, and Tristan and I discussed that while we were writing it, and it was definitely something that informed us during the making of it.

Once you have made the film and you have put it out there for the audience to experience, do you perceive there to be a transfer of ownership?

KRT: As soon as you release your film, go onto YouTube, look at the trailer and the first comment underneath the trailer is: “This is shit! You realise that it is no longer your baby. You have released into the world and some people will hate it and some people will love it. It is a very interesting lesson because no matter how much you love it the audience makes up their own mind. Tristan, what do you reckon?

TRT: I agree! You are releasing it out there into the big bad world and people are going to either love it or hate it. I totally agree with that, and I think you can hone it, and father it for as long as you want, but once you actually get it out there and release it then it is up to the masses mate. It is up to whether they like it or not.

The collaboration between the filmmaker and the audience is a vital one. Wyrmwood has shown a new level of interaction exists through the audience’s active participation to help make the film. How do you perceive the way that film is evolving and the benefits of this level of interaction?

KRT: That is a very interesting question because back in 2010 we shot a scene which we considered was going to be the opening scene of the film. But it turned out not to be – we cut it from the final film. So we released ten minutes of footage online and had a huge response. We were lucky as filmmakers in regards to that we knew we had an audience; a fan base that was waiting for the film for three and a half years. When we went after crowdfunding the anticipation meant people wanted to buy the film ahead of time. So we were very successful in that people bought into this project very early on and we have been interacting with our audience for four years prior to releasing the film. We didn’t release this film nervously because we knew that we had an audience waiting for it. We hoped that it made a bit of money and it got a distributor, but what we didn’t know was that we had a much larger audience than we actually thought. So when we were seeing the tweets from Glasgow, the film premiere in Texas and all of these fans come out of the woodwork…when we premiered in Toronto the film hadn’t even been released, but all these Cosplay’s turned up in costumes that they’d made from the film; from posters. So it is a very interesting time for filmmakers because you can build a fan base without having even shot or finished a film. I am fascinated by the concept because I know a lot about film and film history and this has never occurred to me the Internet has blown the doors wide open in that regard. Obviously the piracy is an issue, and is something that we have to work through, but in terms of being interactive and having a personal relationship with your fans, it has never been better. It is an exciting time to be a filmmaker.

What have you taken away from the experience of your debut feature film, and how will the experience help propel you forward?

TRT: I think momentum is the best lesson that I have learned from making Wyrmwood. You just have to keep up your momentum and keep on moving ahead no matter what, because if you stop then everything just comes to a grinding halt. But if you just keep on going forward, then you are going to be able to make it happen.

KRT: You know what I learned from this whole experience more than anything – it is the simplest possible thing in the world. I learned that I can direct a film and people will like it. Being a filmmaker and as it is my dream hoping – can I, will I be able to do it? Yes I can, and that is a fantastic thing to be able to say. The best lesson you could learn is that you can follow and fulfill your dreams.

The hardest thing that we are going through at the moment is how do we top it. We have had this success; everyone loves the film and it is a cult classic, but now we have to make our second film. In a way it is more important that we get this one right. So now all I am thinking about is the second film. I love Wyrmwood but it’s like we’ve got to get the next one totally right, and we’ve got to build on that. So that is a scary concept.

Interview by Film Frame editor Paul Risker.

You can find Wyrmwood on Twitter here.

|

|

|

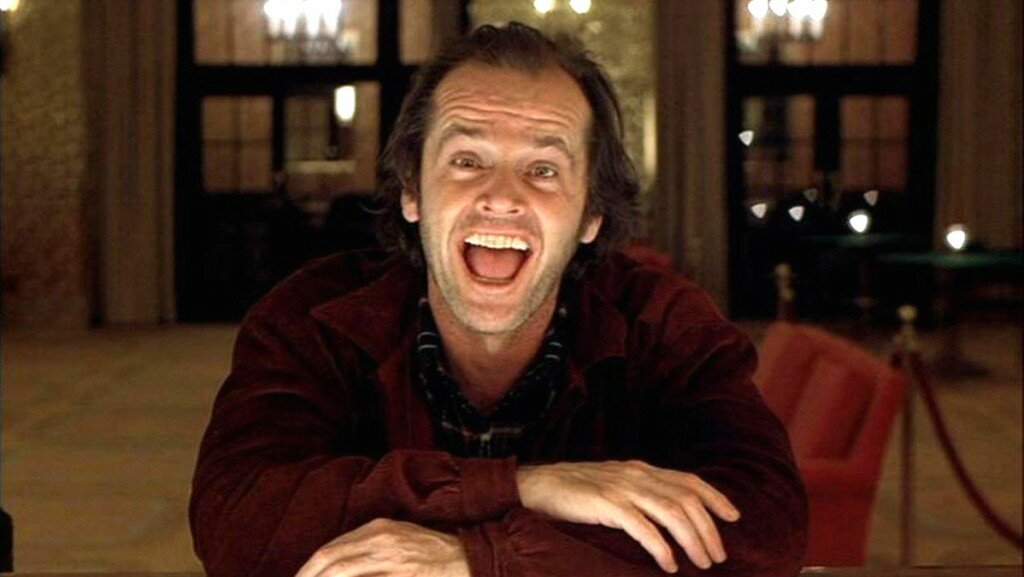

The Strange Case of The Shining

By Paul Risker

In the yearly polls which look to proclaim the ten films that will comprise a list of the greatest films in the history of cinema, or at least the greatest as perceived that year, regardless of decade or year, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather consistently feature near the top. These two films have secured themselves a dominating position, casting their shadow across the heritage of film. Questioning Spanish director Isaki Lacuesta on his list of the top ten films he once contributed to a Sight and Sound poll, with a smile he confessed, “These lists in the end are something very silly. Today I’d make another list… It’s like a game; you just list ten titles.”

Inevitably there is silliness to the critical profession, and star ratings, and polls such as these are the peak. They should never be taken too seriously, but that said they can be indicative of the impact of certain named films on the history of the cinematic art form.

The list of the greatest horror films too has one film that dominates this silly game. Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is the horror genre’s Citizen Kane and The Godfather; the dominating presence within a heritage of horror.

What bolsters the dominating position each of these films holds is a joint approval from the critical establishment and the public.

In contrast to Coppola’s seminal gangster film, Kubrick’s The Shining is not equally representative of the pinnacle of near perfection within the horror genre, as The Godfather is across genre boundaries.

1980: The Release

The Shining was released in the shadow of the coming of age of the ‘Slasher’ sub-genre. Only two short years earlier, ‘Master of Horror’ John Carpenter’s cult hit Halloween brought not only a commercial viability to the ‘Slasher’ sub-genre, but albeit Pauline Kael’s scathing criticism, an otherwise nod of approval from the wider critical establishment. Released in 1980, the same year as Sean Cunningham’s Friday the 13th, a time when horror films were typically fast-paced, Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel of the same name was a patient, slow burn descent into madness, compared to the fast paced stories of psychosis featured in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Black Christmas (1985) and Halloween (1978); all of which were well under the two hour mark.

The Shining was released in the shadow of the coming of age of the ‘Slasher’ sub-genre. Only two short years earlier, ‘Master of Horror’ John Carpenter’s cult hit Halloween brought not only a commercial viability to the ‘Slasher’ sub-genre, but albeit Pauline Kael’s scathing criticism, an otherwise nod of approval from the wider critical establishment. Released in 1980, the same year as Sean Cunningham’s Friday the 13th, a time when horror films were typically fast-paced, Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel of the same name was a patient, slow burn descent into madness, compared to the fast paced stories of psychosis featured in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Black Christmas (1985) and Halloween (1978); all of which were well under the two hour mark.

In hindsight, The Shining was released at a particularly interesting time for the horror genre, as well as cinema in a broader sense, an important piece of horror filmmaking when considered alongside Ridley Scott’s sci-fi horror Alien (1979), and John Carpenter’s Halloween.

Of equal importance, 1980-1982 saw three films suffer a dismissal, only to be re-assessed years later, all three now considered amongst the finest films of the 1980s: The Shining, and 1982’s Blade Runner and John Carpenter’s The Thing. The Shining’s original dismissal upon reflection appears to be a part of a two year trend of the critical establishment falling behind the forward thinking filmmakers, dismissing films that were later reassessed as seminal films of their respective decade within the sci-fi horror, sci-fi noir and horror genres.

It was a case of pure coincidence that saw the release of the haunted house movie in outer space Alien, followed one year later by the haunted house story, The Shining. In 1979 and 1980 the haunted house film received a makeover, first transposing the haunted house for a mining vessel, and later a hotel closed for winter season. The release of these two films back-to-back mirrored the release of Peeping Tom and Psycho in 1960, which were off the back of 1950s sci-fi horror to present man as monster. The Shining is to Alien what Peeping Tom and Psycho were to their predecessors. Further still, alongside Alien and The Thing, The Shining featured an exploration of isolation, to form a trilogy of films between 1979 and 1982 that were to have at the heart of their narratives the theme of isolation. In their isolated settings, each film would terrorise their respective protagonists, though whilst the two companion pieces adopted an alien threat in the form of a physical monster, The Shining used the supernatural and descent into madness, explored sparingly by Carpenter in The Thing through the heightened paranoia of his protagonists.

Equally, just as the ‘Slasher’ sub-genre, as well as the ‘Giallo’ films of Bava and Argento increased the celebration of violence, imbuing the genre with a guilty pleasure for its eager spectators, deriving from the spectacular bloodletting, The Shining can be viewed as a progressive tale, both as a haunted house movie, and a tale of man victimised by malevolent supernatural forces. This was previously explored in two classics of the genre: The Haunting and The Innocents, the latter of which was adapted from Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw, previously adapted into by Benjamin Britten for his opera of the same name. Kubrick’s film updated the haunted house movie from black and white horror to colour, continuing the slow burn simmering suspense contained within these earlier works from which the horror derives. The Shining imbues the haunted house story with a more visceral visual horror, bringing the haunted house movie up to date with the contemporary horror of the late seventies, and early eighties. Kubrick furthers this by inserting a surreal element to his horror, the famous bear sequence, perhaps a pre-cursor to the ‘Lynchian horror’ that lay ahead in the coming decades. In many ways The Shining along with Halloween and Alien update the sub-genres in a more subtle fashion to the European directors Bava and Argento, punctuating the tension with a more controlled subtlety, less bloodletting, more of a physical threat of violence, allowing of course for the occasional more graphic set pieces such as Alien’s chestburster scene.

From Dismissal to Masterpiece

Returning to the notion of the film’s dismissal upon release, there is a common myth regarding its reception. The Shining was in part a success, a worthwhile investment for Warner Bros. The mathematics of the film business states that for a film to make a profit, it must gross more than double its original budget. Compared to Blade Runner and The Thing, two films that were dismissed by the public as well as the critical establishment, The Shining was fortunate enough to discover an audience, most likely deriving from the anticipation that was present to see the adaptation of Stephen King’s bestselling novel. Despite its initial contributions to the genre and the place it occupies in a heritage of horror, combined with its financial success, it fell into the shadow of Halloween and the ‘Slasher’ sub-genre. This may be owed to lack of expectation for Halloween, a low budget and cult phenomenon when compared to the expectation that greeted Kubrick’s horror movie.

Joseph Haydn composed music for his contemporary audience, but every classical composer since, including Mozart and Beethoven were composing for future audiences. Kubrick’s first foray into the horror genre witnessed the auteur finding his present audience, but abandoned by the critical establishment he was forced to wait for them to catch him up. This abandonment along with Stephen King’s initial lukewarm response to the film only served to delay any such immediate acknowledgement of the film as it is believed to be today: a masterpiece of horror cinema.

The immediate metaphor that strikes me whenever I contemplate the irony the passage of time afforded the film, is that The Shining resembles the Phoenix rising from the ashes.

Public opinion, reactions of filmmakers like Martin Scorsese who included The Shining in his list of the scariest horror films, to the critical establishment’s reassessment and continued celebration of the film, perhaps one might say apologetic pandering, has afforded The Shining its dominant position. Now entrenched in this dominant place, it is all in spite of its complicated history, the story of dismissal to masterpiece.

The Psycho Conundrum

If The Shining is, as it is more often than not claimed a horror masterpiece, it is a flawed one; a mix of both failure and success. In this sense it is comparable to the ‘Master of Suspense’s’ foray into the horror genre with Psycho, a tagged on ending with a psychological explanation pertaining to Norman Bates forgiven. This is in spite of exposition being one of the offences critics are more than willing to throw a penalty flag for, and in light of Michael Powell’s mastery at weaving the layers of his psychological horror Peeping Tom, sidestepping such gaping narrative laziness, film criticism is sometimes guilty of looking the other way for certain films and their directors. This has created a scenario in which, whether right or wrong, The Shining remains considered one of horror’s greatest achievements.

The obvious irony of The Shining is just how far removed it is from the frosty days of 1980, when Kubrick was seen to be slumming it in the tawdry genre. Once dismissed it now securely rests, firmly beyond reproach.

This is in spite of its shortcomings, Kubrick’s horror not the near perfect horror film that other films of the genre can claim to be. It raises the question of what this says then about this dominating position, in light of the greatest achievements lack of perfection.

A Heritage of Horror

The horror genre is steeped in a rich heritage, its iconic film not representative of the perfection it rightly deserves. To determine the greatest achievement may be a task that verges on the impossible, but as Chandler described The Great Gatsby as near perfection, one of the finest American novels, should we not be able to call the film that is so often seen as the figurehead of the horror genre, both near perfect, and hence one of the finest horror films? We have created an awkward predicament for ourselves in which this is not possible.

The heritage of horror reaches as far back as to the masterpieces of German Expressionism: The Cabinet of Dr . Caligari, Nosferatu and Faust. The films of Universal Horror following the migration of the horror film to the west coast of America where James Whale became known as the ‘Father of Frankenstein’, and Lugosi and Karloff became horror icons. The monster movies produced have become classics of the genre that terrified audiences for decades. In the 1960s Mario Bava developed the ‘Giallo’ film combining the horror and detective story, further developed by Dario Argento starting with Bird with the Crystal Plumage. Hammer at one time dominated the British horror scene, and the origins of the ‘Slasher’ were spawned from the influences of the psychological thriller, the horror film, and the ‘Giallo.’ More recently Guillermo Del Toro and other Spanish directors have contributed to this heritage, affording us possibly two of the finest horror films of the noughties: The Orphanage and the entry in the Spanish horror anthology 6 Films to Keep You Awake: The Baby’s Room.

. Caligari, Nosferatu and Faust. The films of Universal Horror following the migration of the horror film to the west coast of America where James Whale became known as the ‘Father of Frankenstein’, and Lugosi and Karloff became horror icons. The monster movies produced have become classics of the genre that terrified audiences for decades. In the 1960s Mario Bava developed the ‘Giallo’ film combining the horror and detective story, further developed by Dario Argento starting with Bird with the Crystal Plumage. Hammer at one time dominated the British horror scene, and the origins of the ‘Slasher’ were spawned from the influences of the psychological thriller, the horror film, and the ‘Giallo.’ More recently Guillermo Del Toro and other Spanish directors have contributed to this heritage, affording us possibly two of the finest horror films of the noughties: The Orphanage and the entry in the Spanish horror anthology 6 Films to Keep You Awake: The Baby’s Room.

If there already wasn’t enough of an irony associated with The Shining, originally lost in the shadow of the tawdry ‘Slasher’ sub-genre, it has escaped to cast an impenetrable shadow over the entirety of the heritage of horror, comprising many classic or modern masterpieces.

The Shining most notably suffers from Nicholson’s troublesome opening performance, compounded by Kubrick’s indulgence and failure to craft The Shining into the kind of film he intended it to be. Either that or the film it was supposed to be, a film of coherence and not ‘Lynchian’ ambiguity.

The Shining features an intriguing history. Just as the Overview Hotel looms larger than life in the film, The Shining is reminiscent of that tired expression: “Art imitating life”, although in this case life imitating art. The labyrinth featured in the film’s conclusion is reminiscent of the film itself, a maze of ambiguity that prevents understanding, amidst a narrative of masterful moments to marvel, punctuated with frustrating creative choices that fail to capture the emotional heart of the source material, notably Jack’s self-sacrifice to save his son.

Perfection and imperfections aside, the film as Seghatchian suggests, appeals to both the “obsessive and mainstream audience.” The claims of The Shining being the greatest horror film, an individual favourite, may in fact be the compromise of ambition over perfection. The Shining’s reputation should be susceptible to thought and discussion, the reputation should be capable of being shattered by a whisper, but ever the seductress, the film seduces us into an unbridled affection in spite of these glaring imperfections.

The Shining is an amalgamation of the defining features of the horror genre. It presents the collision between the worlds of the supernatural and our concept of reality, a brooding and immersive atmosphere where the ‘Overview’ becomes more than just a place of suspense and terror for the Torrance family, Kubrick developing it into a character onto itself. It features the dilemma of perspective, of whose we can trust, features one of the finest cinematic performances of madness. It is confident enough to embrace slow burn horror to maximise the horror of mood and atmosphere punctuated by horror imagery of malevolent but equally humorous spirits, decomposing bodies, ominous children, and the blood of past crimes flooding the present. Too the film creates an atmosphere in which not just shocks are used to punctuate the suspense, but comedy, Kubrick walking a fine line, that if exploited correctly can enhance horror; the two interlinked.

The Shining is an amalgamation of the defining features of the horror genre. It presents the collision between the worlds of the supernatural and our concept of reality, a brooding and immersive atmosphere where the ‘Overview’ becomes more than just a place of suspense and terror for the Torrance family, Kubrick developing it into a character onto itself. It features the dilemma of perspective, of whose we can trust, features one of the finest cinematic performances of madness. It is confident enough to embrace slow burn horror to maximise the horror of mood and atmosphere punctuated by horror imagery of malevolent but equally humorous spirits, decomposing bodies, ominous children, and the blood of past crimes flooding the present. Too the film creates an atmosphere in which not just shocks are used to punctuate the suspense, but comedy, Kubrick walking a fine line, that if exploited correctly can enhance horror; the two interlinked.

Just as Beethoven understood and hence infused his music with expectation, Kubrick masterfully uses expectation, something of which it is a pre-requisite of any ‘Master of Horror’ to be able to employ, and maximise to full effect. But Kubrick imbues The Shining with any number of metaphorical interpretations that can be derived from the subtext, the subject of the recent documentary Room 237. The Shining is inevitably one of the finest looking horror films, high production values, not made on the fringes, but one of a handful of films such as The Omen with an A-list cast and a generous budget.

To assert that these qualities define The Shining as horror’s greatest achievement is naïve. Ginger Snaps is a modern horror masterpiece structured around a metaphorical subtext. John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London perfectly blends comedy and horror, and in the vein of The Shining it is simultaneously horrific, suspenseful and funny. Landis creates a collision between perceived reality and the bordering supernatural world. Robert Wise’s The Haunting’s subtext asks the question: is it the house or the protagonists who are haunted? The Innocents is equally one of the finest looking horror films, and one of the most rewarding slow burn suspenseful tales of malevolent spirits terrorising innocent souls. Not to mention possibly the finest horror film: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, rife with metaphor, a treat to the eyes and ears, a brilliant early tale of madness and the questions of the trustworthiness of perspective, of morality and of innocence within the social structure. The Shining may comprise more of these elements than any other horror film within a singular narrative, but Robert Weine’s German Expressionistic masterpiece is equal to Kubrick’s attempt at horror, near perfect, and one of the finest horror films ever made. In fact the visual world of Caligari, full of jarring angles to depict fractured psyches is just as rich as The Shining’s Overview Hotel. It should not be so readily assumed that The Shining stands tall above all other horror films, many rivalling its imperfection with near perfection.

horror masterpiece structured around a metaphorical subtext. John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London perfectly blends comedy and horror, and in the vein of The Shining it is simultaneously horrific, suspenseful and funny. Landis creates a collision between perceived reality and the bordering supernatural world. Robert Wise’s The Haunting’s subtext asks the question: is it the house or the protagonists who are haunted? The Innocents is equally one of the finest looking horror films, and one of the most rewarding slow burn suspenseful tales of malevolent spirits terrorising innocent souls. Not to mention possibly the finest horror film: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, rife with metaphor, a treat to the eyes and ears, a brilliant early tale of madness and the questions of the trustworthiness of perspective, of morality and of innocence within the social structure. The Shining may comprise more of these elements than any other horror film within a singular narrative, but Robert Weine’s German Expressionistic masterpiece is equal to Kubrick’s attempt at horror, near perfect, and one of the finest horror films ever made. In fact the visual world of Caligari, full of jarring angles to depict fractured psyches is just as rich as The Shining’s Overview Hotel. It should not be so readily assumed that The Shining stands tall above all other horror films, many rivalling its imperfection with near perfection.

The Shining begins with what is alleged a descent into madness, but Nicholson’s opening scenes depict a creepy and unsettling air to his character. What the film actually explores is only the descent into madness to a point, Kubrick and Nicholson miscuing on the opening tone of the film. The film concludes in a haze of ambiguity, a shot of the photograph that brings a lack of clarity and leaves us with unanswered questions. The stumbling block for Kubrick is that he indulges in ambiguity, confusion, within a narrative that is meant to be clearly understood by the point of it’s denouement. The fact it isn’t betrays Kubrick’s intention to achieve something out of his reach, something director David Lynch exploited throughout his cinema in the ensuing decades. Kubrick’s failure is his indulgence. King’s original qualms were fair, constructive criticism of an adaptation that for all its success was undermined by its shortcomings.

The Shining is a film naively loved not in spite of its imperfections, but because of its perfection. It is all too often an unrealised compromise by critics and spectators of ambition over perfection.

The Outsider

Discussing with ‘Master of Horror’ Don Coscarelli Incident Off and On a Mountain Road, he offered his own observation of the perception of horror in the U.S. “I don’t know exactly how it is in the UK, but certainly in the U.S. horror is one step above pornography, the way people treat it.” The great American auteur John Carpenter has asserted that “In England, I`m a horror movie director. In Germany, I`m a filmmaker. In the US, I`m a bum.” The use of the word pornography links Coscarelli and Carpenter. Carpenter once remarked that horror directors are seated one row from the back, the only people seated behind tany further back from them are pornography directors; paraphrasing of course.

The greatest tragedy of The Shining occupying this dominating position is that it is directed by an outsider. Kubrick’s cinema may have incorporated aspects of horror, but he does not belong to the fraternity of the ‘Masters of Horror.’

Kubrick’s contribution at the turn of the 1980s is valuable, enriching horror and cinema in a broader sense with what is both a fine looking film and ambitious horror film that deserves to be applauded. It is a film that despite its imperfections seduces; a film loved in spite of its imperfections. Whilst many applaud its ambition, simplicity as Clive Barker stated is “Genius.” Therefore, as much as I appreciate The Shining, I would rather see the simplistic perfection, or just near perfection over ambitious imperfection.

One of horror’s finest films perhaps; but if it is horror’s singular greatest achievement, it is riddled with a naïve appreciation, an unwillingness to perceive its imperfections. Any number of near perfect classics such as The Orphanage, An American Werewolf in London, Ginger Snaps, Frankenstein, Peeping Tom, The Innocents, Halloween, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and wonderfully creative tales such as The Addiction are overshadowed. These directors are too often perceived to work in a tawdry genre, and they cannot look to one of their own dominate the horror list, instead usurped by an outsider.

It must be a comfort for those who perceive the genre so negatively to have a horror film starring Nicholson, and directed by a great auteur such as Stanley Kubrick. They serve to bring respectability to the genre. It is hard to imagine the BFI contemplating celebrating an Argento film in such a way as they did The Shining, or even Bava’s Bay of Blood. But perhaps that is why horror belongs on the fringes, embraced by a loyal following. We love it because it is viewed with such disdain in the mainstream, never fully accepted or embraced. It is a subversive genre that just compels us to love it all the more. It’s a pity that horror can’t have a film in a dominating position equal to The Godfather; the real tragedy out of all of this.

Paul Risker is the editor of Film Frame, the new website is in progress however he can be found on Twitter here.

Our Favourite Horror Films (Part 2)

Carrie (Brian De Palma – 1976)

The opening of this film is brilliant, the soft light, the music, slow camera, it gives you a sense of the vulnerability of Carrie White. The film slowly builds to the climax which is just fantastic. The pace of the final scene is just wonderful as it plays to the melodrama of the first two acts in which the drama works as an emotional anchor. The horror is entirely visual and doesn’t leave much to the imagination, but the slow build is pitched perfectly by director Brian De Palma.

The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy – 1973)

The iconic ending blew me away when I first encountered this twisted tale of religious perversion and it remains one of the most remarkable scenes in horror filmmaking. Edward Woodward (who is sensational in the lead) has a look of pure terror as the realisation of what is about to happen to him dawns and it burns into your brain. Christopher Lee is, as ever, on exquisite form as the deranged Lord Summerisle and plays the perfect foil for Woodward’s puritanical copper. Deliciously (and refreshingly) unafraid of its Britishness, this has a good story, a pleasing ambiguity and even knowing the final outcome doesn’t prevent total delight in repeat viewings.

Misery (Rob Reiner – 1990)

Better than the source novel? I reckon so, and that is to take nothing away from Stephen King’s source novel. This brilliant two-hander positively drips with tension. The best scene is, in my view, not the infamous ‘hobbling’ but when Annie accidentally knocks over her drugged wine and James Caan’s reaction. Kathy Bates is sublime as the terrifying Annie Wilkes (‘Hush…my darling’) but Caan is equally good (the age old debate of having the understated role). A film which explores the darker side of fan culture pre the internet, uses its remote wintery setting. And the haunting use of ‘I’ll be seeing you’ in the final scene is a match Dr. Strangelove’s ‘We’ll meet again’

Peeping Tom (Michael Powell – 1960)

Aspects of voyeurism are superbly explored in this brilliant chiller that is a real case for the argument that they don’t make em like they used to. Were this made today it would probably be a found footage film, high on blood and editing but most likely without the substance of this brilliant masterpiece.

Ravenous (Antonia Bird – 1999)

A special mention for the late Antonia Bird who was a deeply under-appreciated talent. I can’t believe she wasn’t offered more work than she produced, as this horror-Western really is quite something. Ostensibly a tale of cannibals set against the backdrop of the American Civil War, the film goes a lot deeper than that, exploring such varying themes as the onslaught of modernisation, spiritual bankruptcy and man’s consuming desire for progress. The story never goes where you think it will, surprising with both its plot developments and character studies (Guy Pearce’s cowardly Captain Boyd is a masterstroke in creating the anti-hero, while Robert Carlyle is magnificent as the enigmatic Colquhoun). Featuring one of my favourite all-time scenes where a group of soldiers devour a pile of steaks like rabid animals, this delight of a film is bolstered by Bird’s deft touches in sound design, composition and storytelling nous, while Michael Nyman and Damon Albarn’s unusual score traverses the mood expertly. A treat.