ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE COEN BROTHERS: SUBVERTING THE ROM-COM GENRE.

The vast majority of romantic comedies will follow a relatively predictable structure. Boy meets girl (a ‘meet-cute’ more often), boy meets girl again (a more in depth get-together), boy and girl actually get together, boy and girl split up and finally, boy and girl realise their feelings and get together for good. There are complications along the way – careers, third parties, parents etc. – but come the end, love conquers all.

Yet what happened next? The credits roll and the audience goes home happy that the two people who were meant to be together ended up together. What of the couple though? Do they stay together forever? Do they get married and have a wonderful life? Or do they get bored with one another or drift apart? Could, conceivably the central marriages in Sam Mendes films American Beauty and Revolutionary Road have started with much joy and love in the way many romantic comedies end?

Ideally, we’re not meant to ponder on this. It ruins the illusion, the magic of the movies. As Basil Exposition from Austin Powers would say – try not to think about it too much and just enjoy yourself. The happiness of the relationship is preserved in an almost inverse way to Romeo & Juliet where the titular couples tragic demise preserves their short relationship for all the ages.

Some films do try and give us a glimpse of ‘what happens next’ often via a montage or clip set some time after the main bulk of the action. Notting Hill ends with Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts sitting together in a park, both happily married and her obviously pregnant. Wimbledon shows Paul Bettany and Kirsten Dunst teaching their children to play tennis. Maid In Manhatten shows us a magazine cover from boasting that Ralph Fiennes and Jennifer Lopez are ‘Still together – One year on!’ It’s a way of extending the fantasy.

Yet when films play with the convention of genre, it can make for something rare and unique and there have been few better genre-benders in recent cinema than the Coen brothers, Joel and Ethan. Bizarrely, their 1987 screwball comedy Raising Arizona actually does conform to the aforementioned structure yet it brilliantly subverts it. For the opening ten minutes serve like a whirlwind rom-com. H.I (Nic Cage) and Ed (Holly Hunter) meet and get married all before the opening credit has rolled, just ten minutes into the film. It’s an absurd set-up that we often get in romantic comedies- she is a cop and he is a criminal and they meet via his appearance in a police line-up. The rest of the film then follows their attempts to start a family – by kidnapping the son of a furniture tycoon. It’s a romantic comedy that manages to squeeze the standard bulk of a romantic comedy into its opening gambit before stretching out what is traditionally a closing montage into the bulk of a ninety minute film. It’s a simple but effective trick that makes for a unique film. It reminds us of the difficulties that may lay ahead, post-wedding.

Similarly, with Intolerable Cruelty the brothers made a screwball romantic comedy that also follows the standard structure. However, the key difference is that Marilyn (Catherine Zeta-Jones) plans much of the plot out herself. She sets things up so that she can meet Miles (George Clooney), have him fall in love with her and get together before she divorces him and walks off with a healthy cheque. The only un-planned element of the whole thing is that come the end, she actually does fall in love with Miles – love conquers all, even in the bitter world of divorce lawyers and gold-diggers. It may be more conventional, but its application is almost post-modern.

Of course part of the reason that many romantic comedies do culminate in a wedding or a moment of union is that they often represent the happiest point of a relationship. Many relationships do run a joyful course with, as mentioned, many films demonstrating a snapshot of life after sunniest of moments but some of course do not. In life people get bored, drift apart, have affairs, decide they’re not right for each other or discover things about the other that they don’t like. Some relationships end in bitter separations with the couple having nothing good to say about one another. Romantic films rarely deal with this idea – with a notable exception of Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

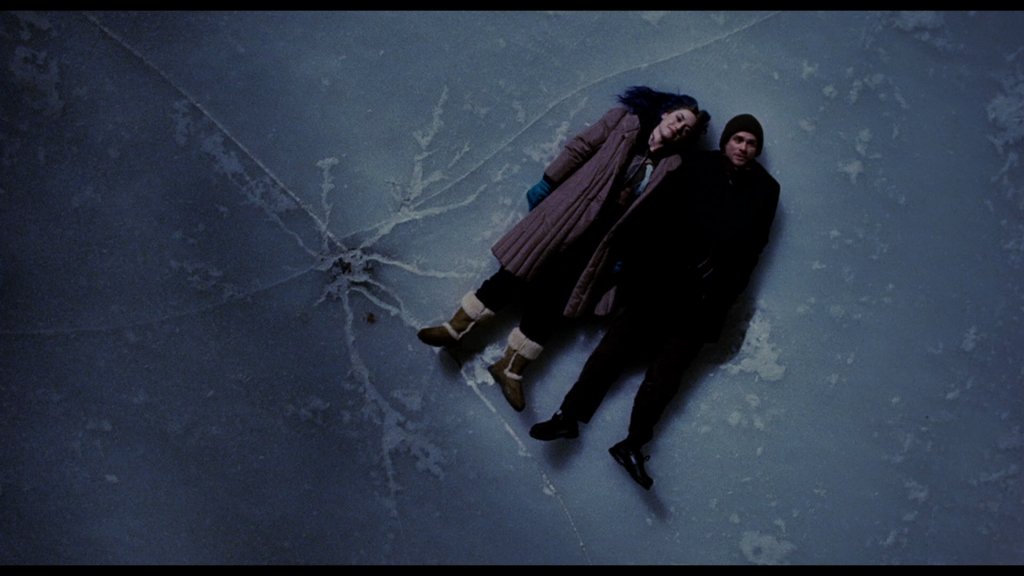

Clementine (Kate Winslet) and Joel (Jim Carrey) are experiencing one such break-up leading to him visiting Lacuna, Inc. to erase all memories of said relationship. However, as the process takes place, the bad memories from later in the relationship are the first to go leaving Joel with happy memories of his time with Clementine. These memories are ones he forgot he had and he realises he doesn’t want them erased. In showing the relationship in this way, the film is doing something unique – it is working backwards. Instead of leading up to the happiest moments, it is working back towards them. At a relationships start we don’t know they’re coming – at the end we’ve forgotten they were there.

It’s a shame that there aren’t more examples of love stories which subvert the genre in the same ways as the aforementioned films. While the not-so-secret formula works well for audiences and bean counters alike, it takes the likes of Raising Arizona and Eternal Sunshine to show up the most predictable of genres which is, ironically, about the most un-predictable human emotion.

A special mention goes to Philip Seymour Hoffman and his portrayal of Dean Trumbell, the ‘Mattress Man’. A hilarious performance of a character that is almost the antithesis of Egan, a man that presents Egan with an opportunity to face up to himself. In challenging the Mattress Man Egan validates himself, he’s the good guy, and he becomes hero he deserves to be.

A special mention goes to Philip Seymour Hoffman and his portrayal of Dean Trumbell, the ‘Mattress Man’. A hilarious performance of a character that is almost the antithesis of Egan, a man that presents Egan with an opportunity to face up to himself. In challenging the Mattress Man Egan validates himself, he’s the good guy, and he becomes hero he deserves to be. One of the key selling points of romantic comedies is the guaranteed ‘feel-good’ factor that the audience is going to experience come the end. Romantic Comedies tend to be crushingly formulaic wherein a couple meet, get together and break-up only to realise their true feelings and unite just before the closing credits.

One of the key selling points of romantic comedies is the guaranteed ‘feel-good’ factor that the audience is going to experience come the end. Romantic Comedies tend to be crushingly formulaic wherein a couple meet, get together and break-up only to realise their true feelings and unite just before the closing credits.